If you’re a biker, you know that Hollister is not just an über-hip clothing line for spoiled mall rats. No, Hollister — a small farming community in Southern California southeast of San Jose — is the birthplace of the American Biker, that enduring trope perpetuated by media and entertainment ever since that hot July 4th weekend of 1947, when a ‘riot’ broke out during a motorcycle rally.

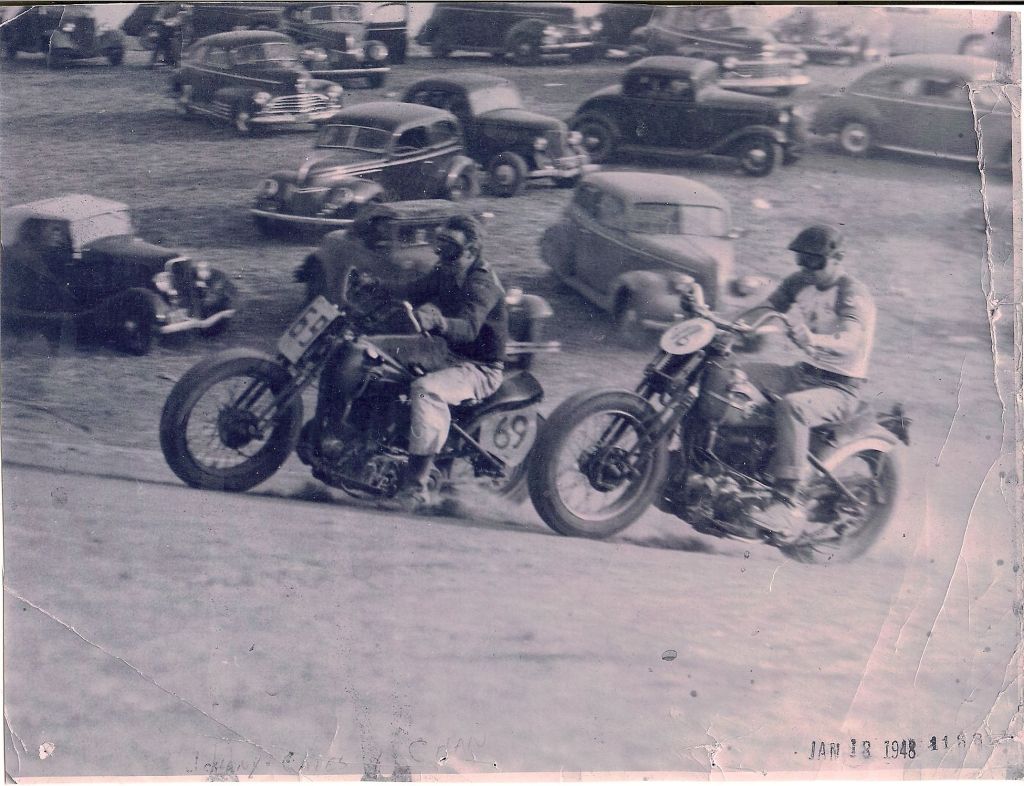

The scene at Hollister was a familiar one: a small town, eager to bring in tourists who might spend money at local businesses, built a racetrack at Veteran’s Memorial Park, and began hosting motorcycle races and ‘Gypsy Tours’: popular family-friendly gatherings sponsored by the American Motorcycle Association, as it was then known. The events were well-attended and profitable, and in most cases the worst local authorities had to deal with was a few Drunk and Disorderly arrests and some hospitalizations due to injuries suffered in motorcycle crashes on and off the track.

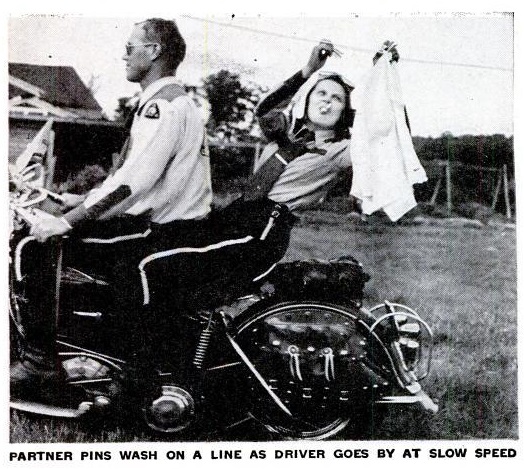

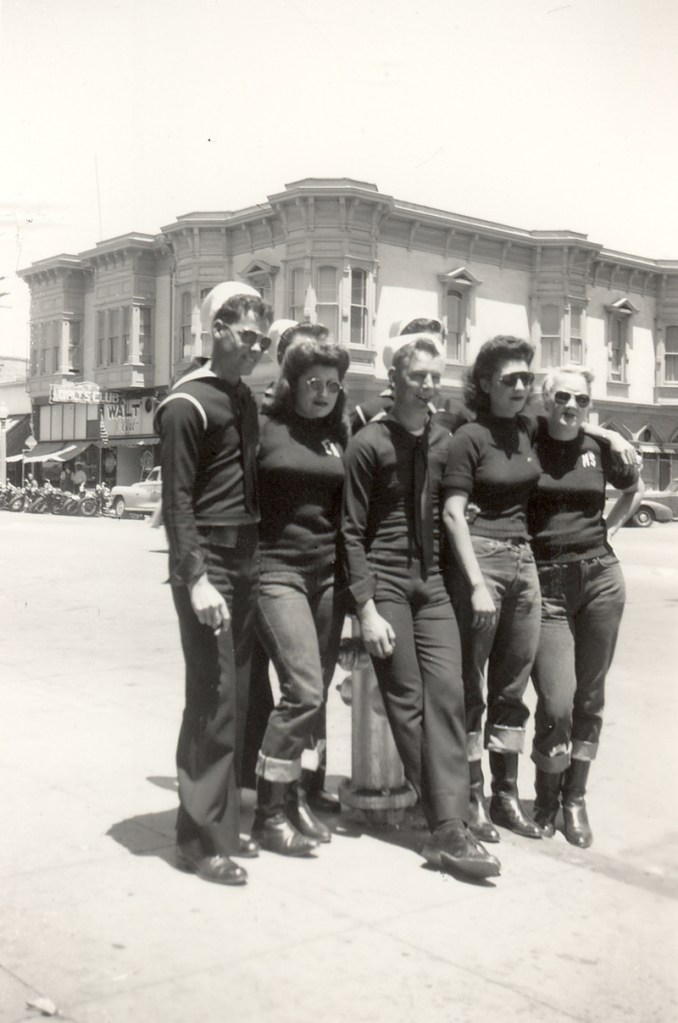

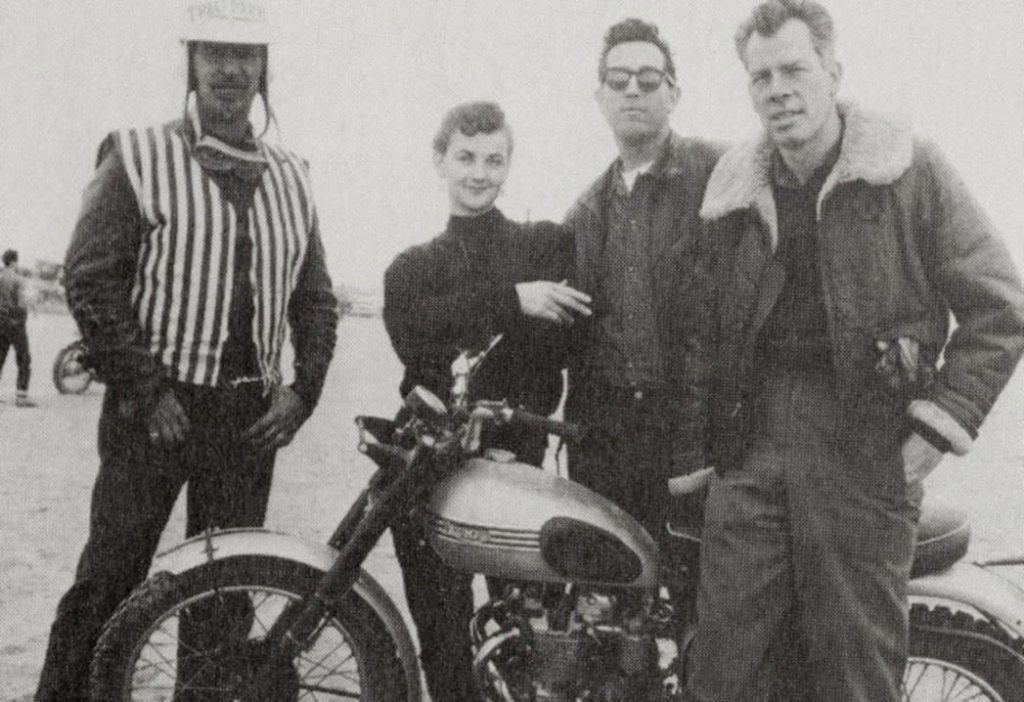

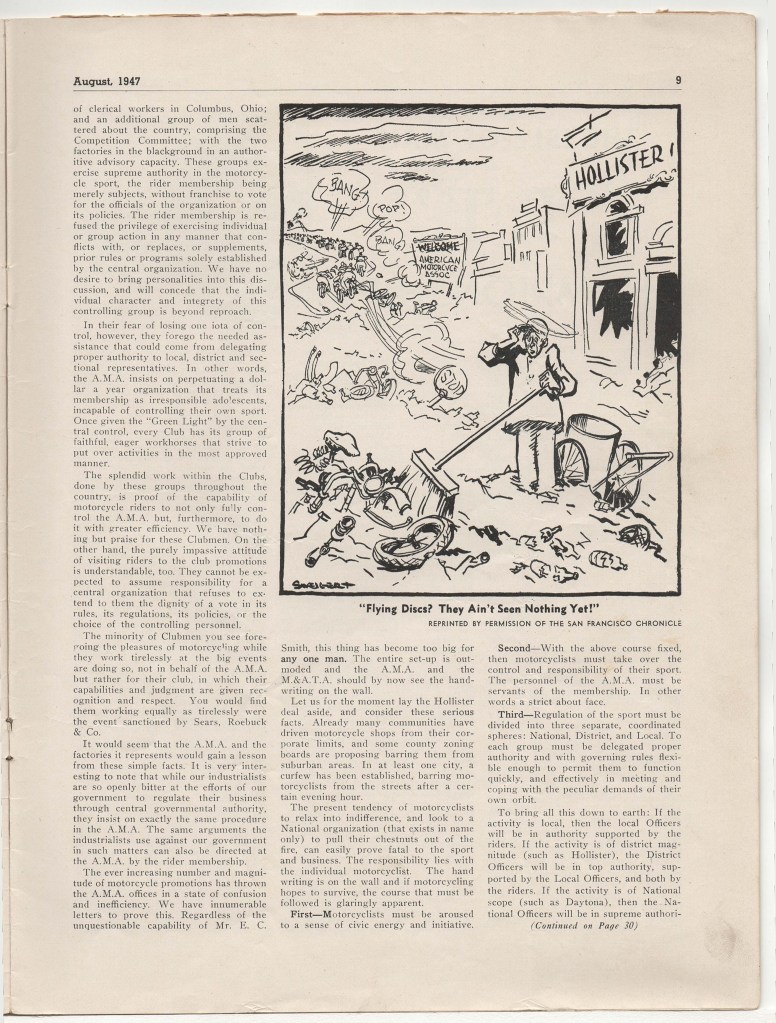

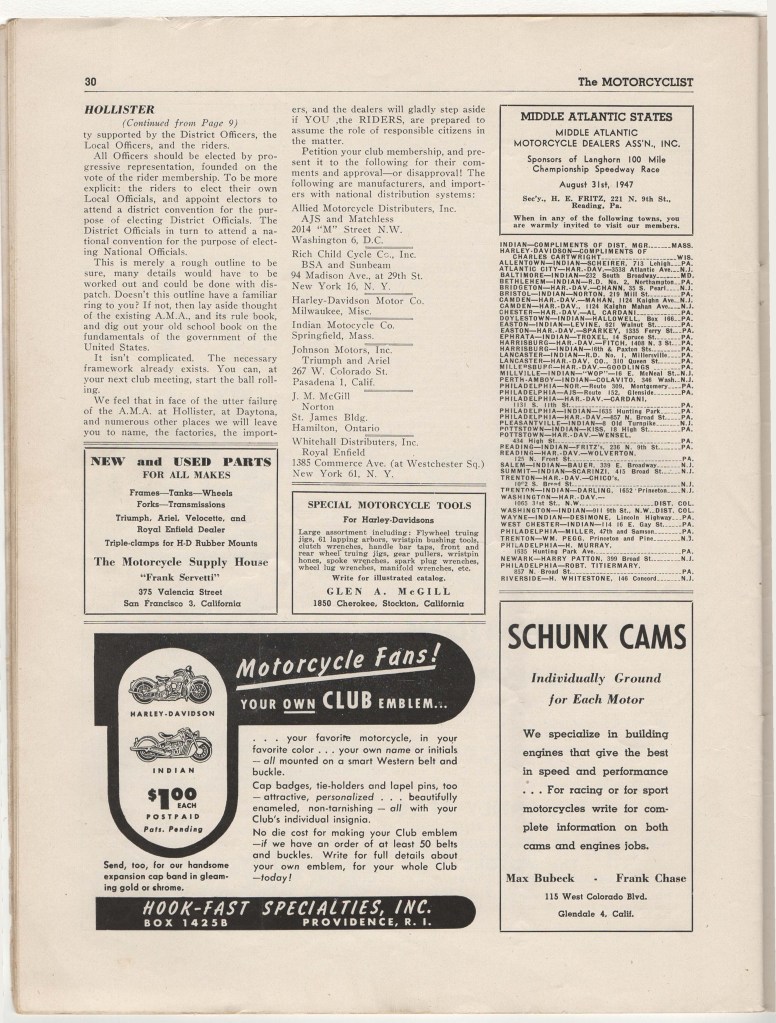

However, the 1947 event, one of the first held since the guns of World War Two fell silent, drew a new breed of rider. These were not the nice Mom-and-Pop ‘straight’ clubs pictured above, that frequently appeared at these events in matching uniforms, riding pristine motorcycles kitted out with numerous factory-approved accessories.

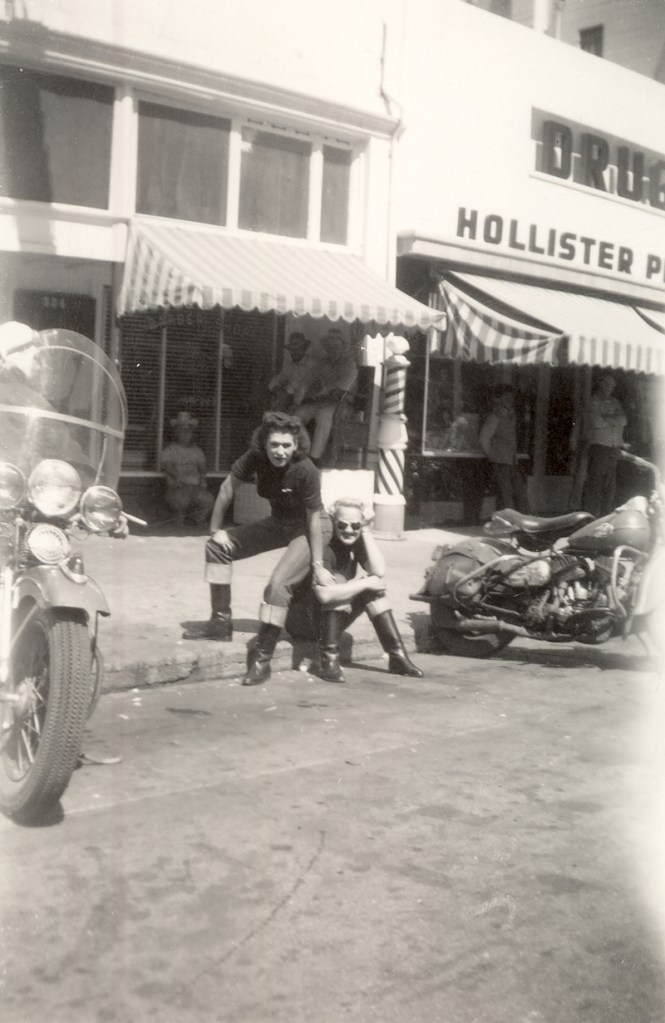

No, these were rough, hard-bitten young men — most of them combat veterans who had seen the worst the world had to offer in the killing fields of Europe and the South Pacific — and they roared into town en masse aboard stripped-down, hopped-up motorcycles unlike anything those at Hollister had ever seen before.

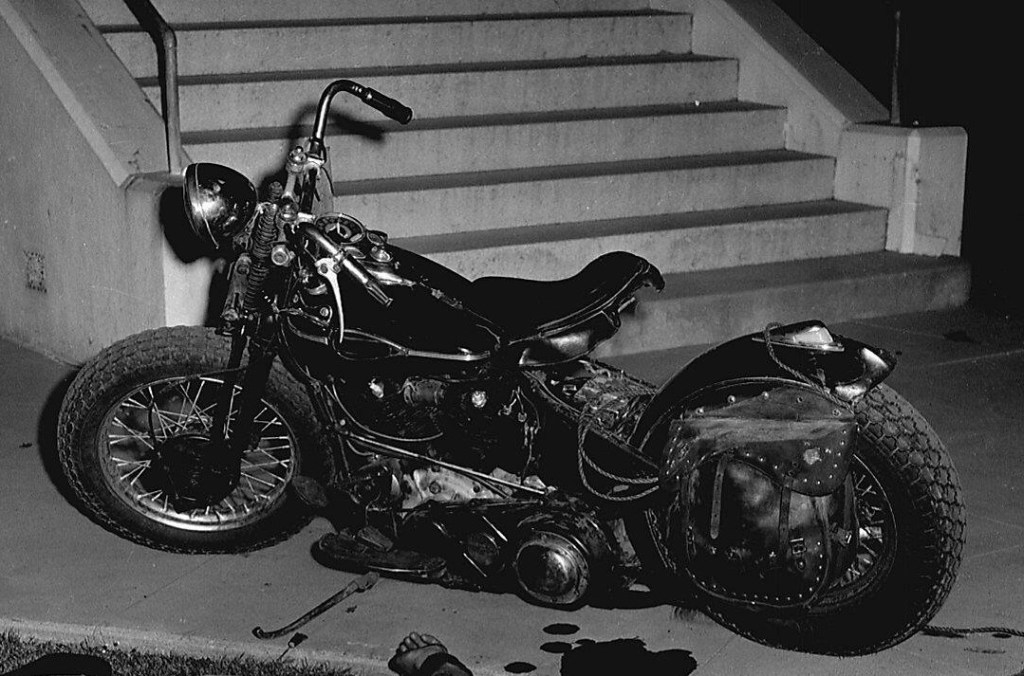

These were rattletrap bombers with front brakes and fenders removed, and rear fenders ‘bobbed’ as short as possible. Chain guards, windshields, engine guards, saddlebags — anything that might increase weight and wind-drag, and slow the machines down — were all shitcanned in favor of better performance, until all that remained was the bare essence of a motorcycle: a massive engine, rigid frame and springer forks, two wheels, a petrol tank and a saddle.

These men also came sporting motorcycle club sweaters or jackets with new, more menacing names — Boozefighters, Thirteen Rebels, Galloping Goose (in military argot the ‘goose’ was the upraised middle finger we call ‘the bird’) and more — and they came not to sit docilely in the stands watching as racers on the track went round-y-round, but to ride and race and party themselves, and that is exactly what they did.

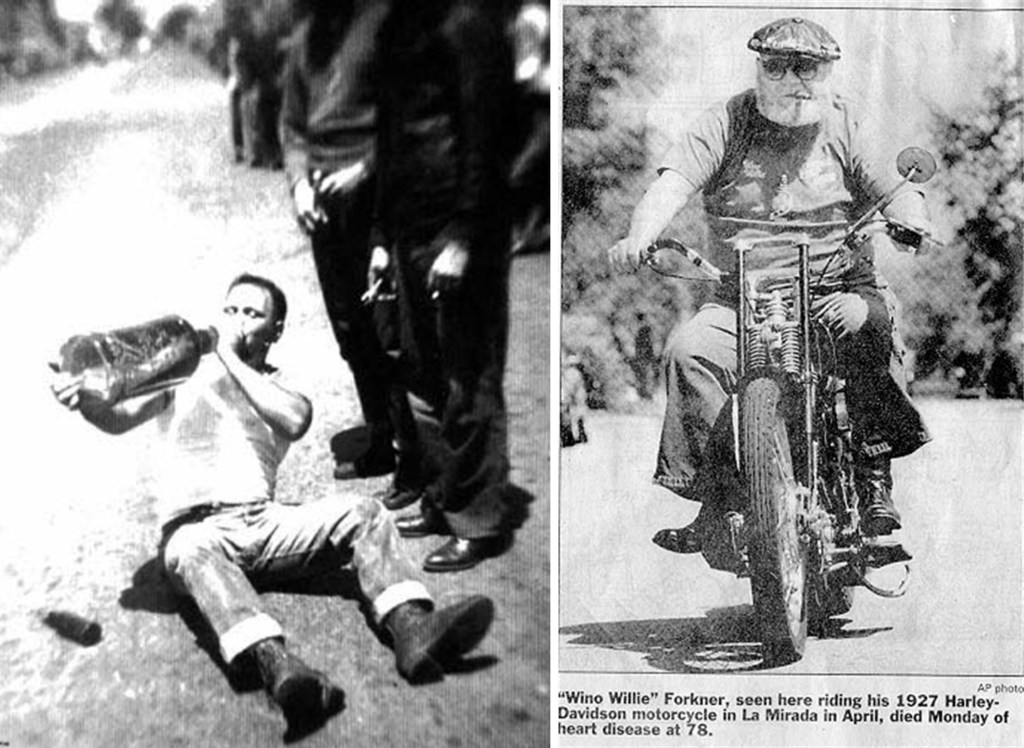

The Boozefighters MC, led by ‘Wino Willie’ Forkner, described itself as a drinking club with a motorcycle problem, and did their level best to live up to that claim. Other clubs, in turn, tried their best to keep pace.

THE RIOT

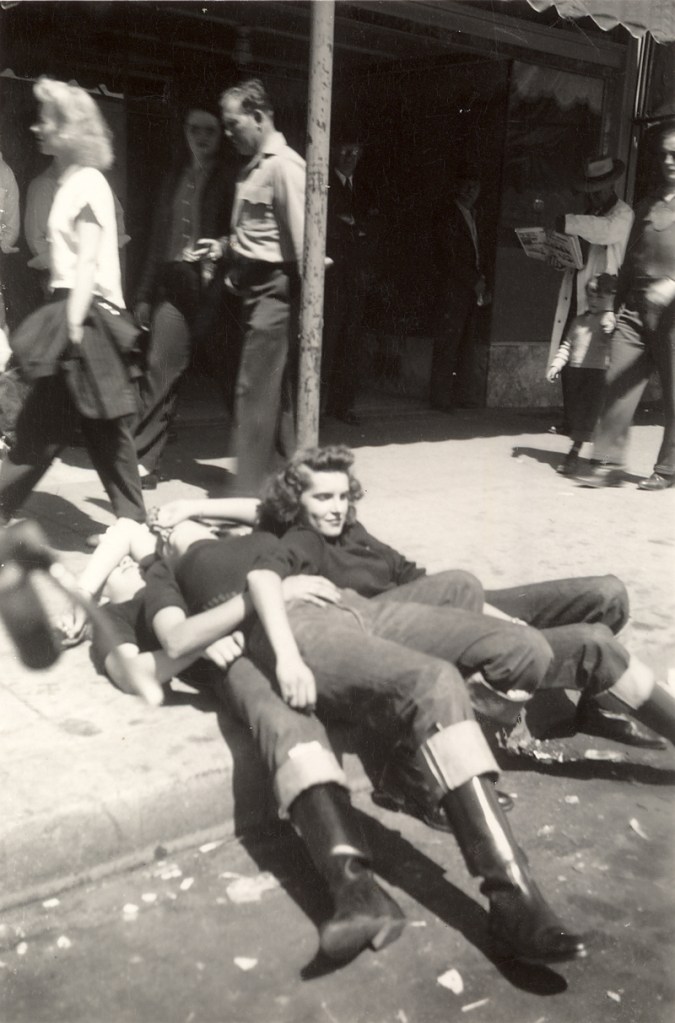

The much-ballyhooed ‘riot’ was really nothing more than a lot of rowdy behavior along Hollister’s main drag, including impromptu drag races and riders doing doughnuts in the street, and raucous drinking in the bars. At one point, it’s reported that a rider did pilot his motorcycle into a bar. In the tumult, some furniture and glassware were damaged, and promptly paid for by the offender.

Still, local law enforcement felt overwhelmed, and called for reinforcements from neighboring counties and the California Highway Patrol. The cops geared up, corralled the partying bikers on the main drag, and commandeered a flatbed truck for use as a bandstand. They pressed a dance band into service, and the rest of the night proved playwright William Congreve’s contention* that ‘Music has charms to soothe a savage breast.’

NEWS COVERAGE, MONDAY, JULY 7, 1947

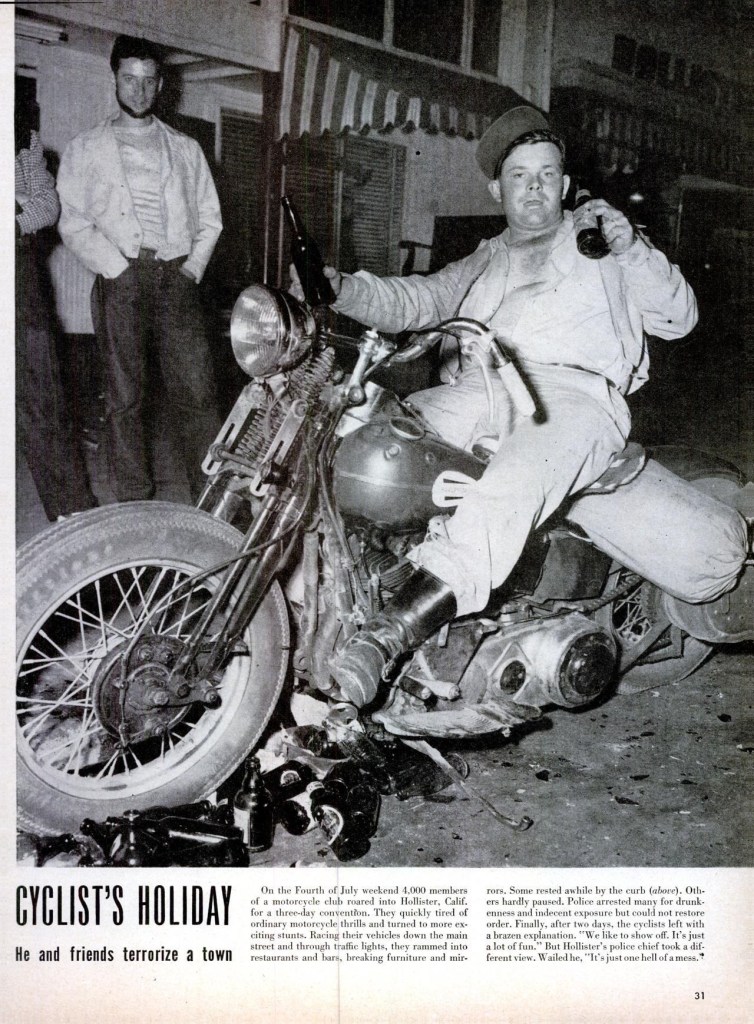

CYCLIST’S HOLIDAY, LIFE, JULY 21, 1947

However, at around the time the band began to play, photographer Barney Peterson arrived in town. Peterson was a freelancer dispatched by The San Francisco Chronicle. His brief was to bring back pictures of the reported mayhem, but all he found was a street filled with happy dancing bikers and civilians, a parking lot full of motorcycles, and a few riders sacked out for the night on the courthouse lawn. In other words, b-o-o-o-o-ring!

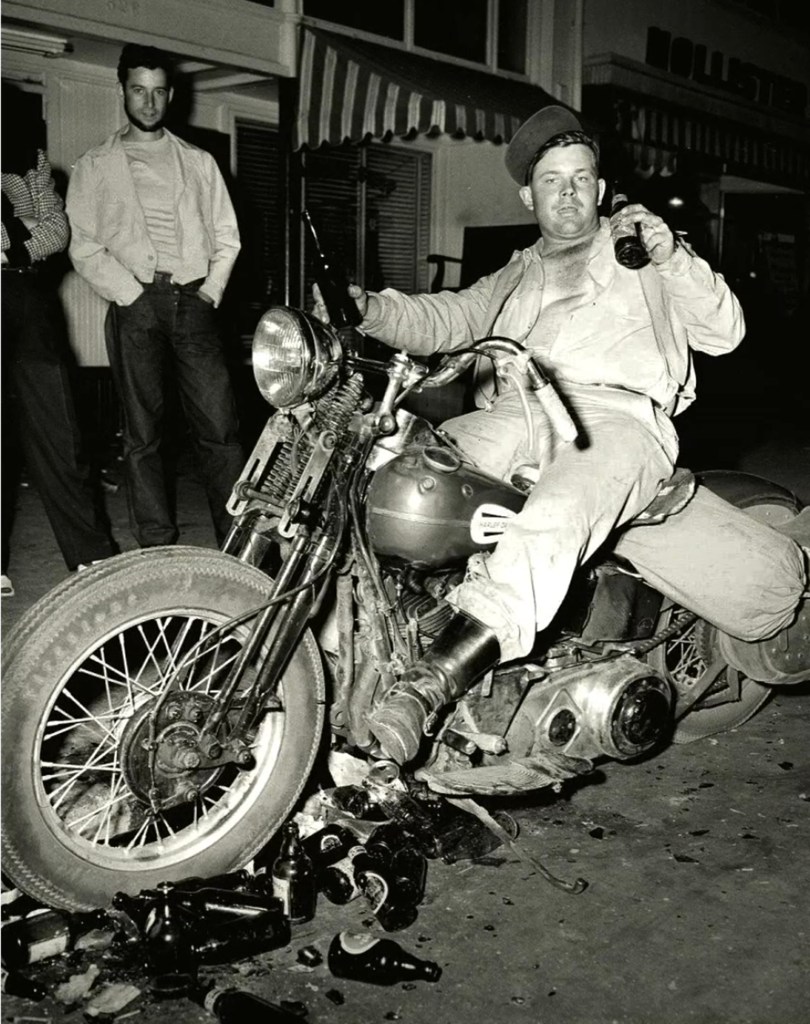

Desperate to preserve his commission, Peterson improvised. As eyewitnesses confirm, he found a motorcycle parked at the curb — a stripped-down Harley-Davidson knucklehead with no front fender, and a seaman’s bag tied across the rear fender behind the saddle.

Perfect!

He carefully arranged a bunch of empty beer bottles on the street around the motorcycle, even cadging some from a nearby café, to symbolize the debauchery he assumed had taken place prior to his arrival.

Yeah, that will do!

Finally, he recruited a fellow named Eddie Davenport to climb aboard the artfully staged motorcycle and pose for some photographs.

Bingo! The editor’s gonna love it!

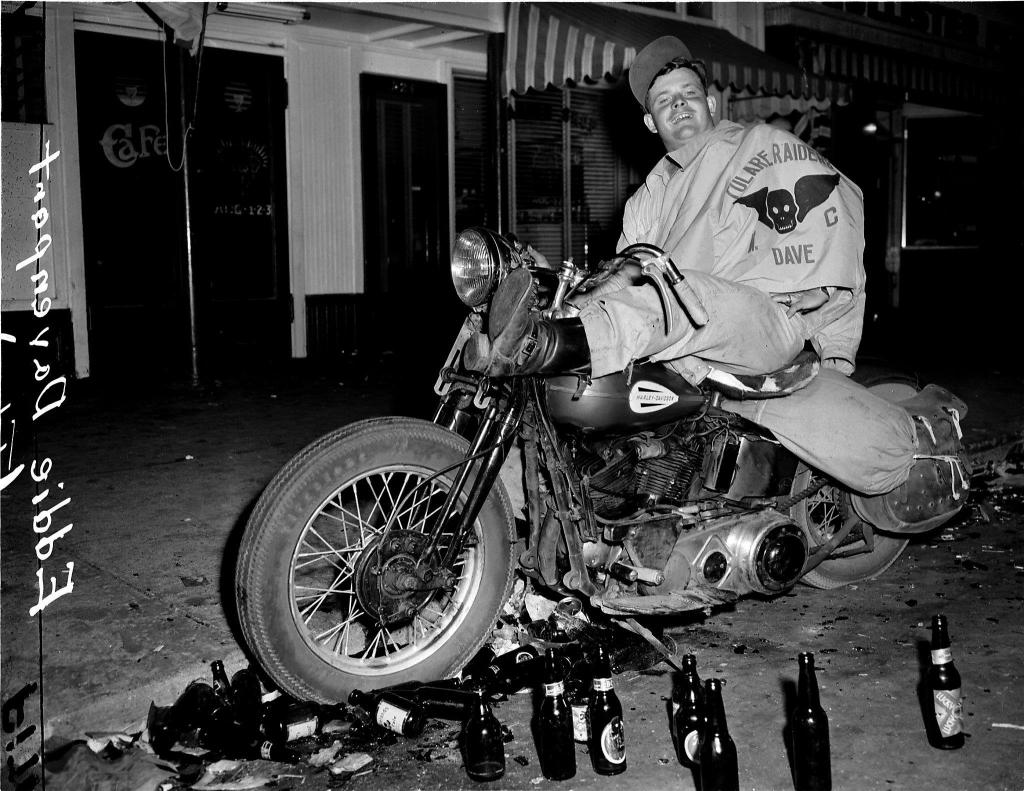

A series of images were made, including the most infamous: the ‘Cyclist’s Holiday’ photograph (above) which the magazine LIFE published in their July 21st issue, above an overheated blurb about the ‘4000 cyclists’ who allegedly ran amok in the peaceful city of Hollister. Barney Peterson’s posed and staged photo of the man identified as Eddie Davenport — he of the slack-jawed, glassy-eyed gaze and two-fisted drinking style pictured above — struck terror into the hearts of pearl-clutching newspaper and magazine editors, chiefs of police and other dignitaries across the nation. Another Peterson creation showed Davenport holding a club jacket belonging to a member of the Tulare Raiders Motorcycle Club named Dave.

For a long time, I believed Eddie Davenport was a nonrider recruited by Peterson for the infamous photo. However, I have recently read reports that ‘Dave’ (as lettered on the club jacket in the photo below) was actually Davenport’s road name, and that Eddie Davenport was a bona fide member of the Tulare Raiders MC. My apologies to Mr. Davenport if I mischaracterized him.

Finally, whatever art or deceit the photographer may have employed, Peterson’s editor did love his photo just as he’d hoped, but they weren’t alone. The photograph hit the wire services, and was immediately picked up by LIFE.

THE REACTION, LIFE, AUGUST 11, 1947

The response to LIFE‘s publication of Peterson’s staged photograph was immediate. Three weeks later, the magazine’s August 11th issue included Letters to the Editors from motorcyclist Charles A. Addams, film star and cyclist Keenan Wynn, and Paul Brokaw, who edited the magazine Motorcyclist at the time.

All three correspondents complained of the negative coverage.

Mr. Addams wrote that the 4000 riders reportedly in attendance were not members of a single club, as the magazine alleged; that 50% were members of the American Motorcycle Association and the other 50% ‘mere motorcyclists out for a three-day holiday’; and that roughly ‘500 made the event the debacle that it was.’ I checked, and it appears certain Mr. Addams was not the infamous New Yorker cartoonist who created The Addams Family. How cool would that have been? 😏

Keenan Wynn, who later took film star and fledgling desert racer Lee Marvin under his wing, and showed Steve McQueen what dirt bikes were for, wrote ‘I have taken it upon myself to… straighten out what will obviously be an extremely bad impression of motorcyclists.’ He went on to decry the reckless behavior of the wild ones at Hollister, and noted that riding under the influence ‘as our friend in the picture seems to be doing, is one of the fundamental “don’ts” of riding…’ Wynn also felt obliged to cite some examples of ‘safe and sane Hollywood riders,’ like Clark Gable, Randolph Scott, Ward Bond and Andy Devine.

Motorcyclist Editor Paul Brokaw expressed his shock at the photograph, and was perhaps the first in print to call Barney Peterson out for his chicanery, noting that the picture ‘was very obviously arranged and posed by an enterprising and unscrupulous photographer.’ Brokaw also called out the ‘mercenary-minded barkeepers’ who continued to serve obviously intoxicated customers, and the ‘small percentage’ of riotous motorcyclists, ‘aided by a much larger group of nonmotorcycling hellraisers,’ who actually caused all the fuss.

Brokaw went on to damn LIFE for ‘sear(ing) a pitiful brand on the character of tens of thousands of innocent, clean-cut, respectable, law-abiding young men and women who are the true representatives of an admirable sport.’

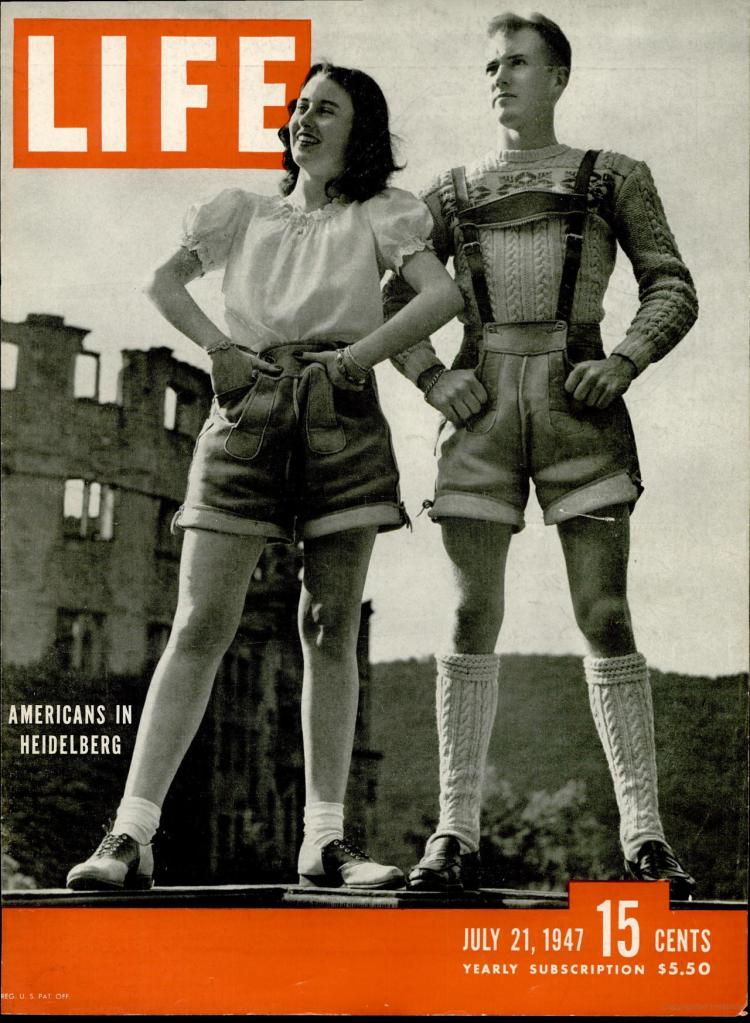

LIFE responded to the criticism by including, in the same issue, a lengthy ‘presentation of law-abiding, respectable motorcyclists,’ which included photos of Mom-and-Pop clubs and motorcycling fashion trends.

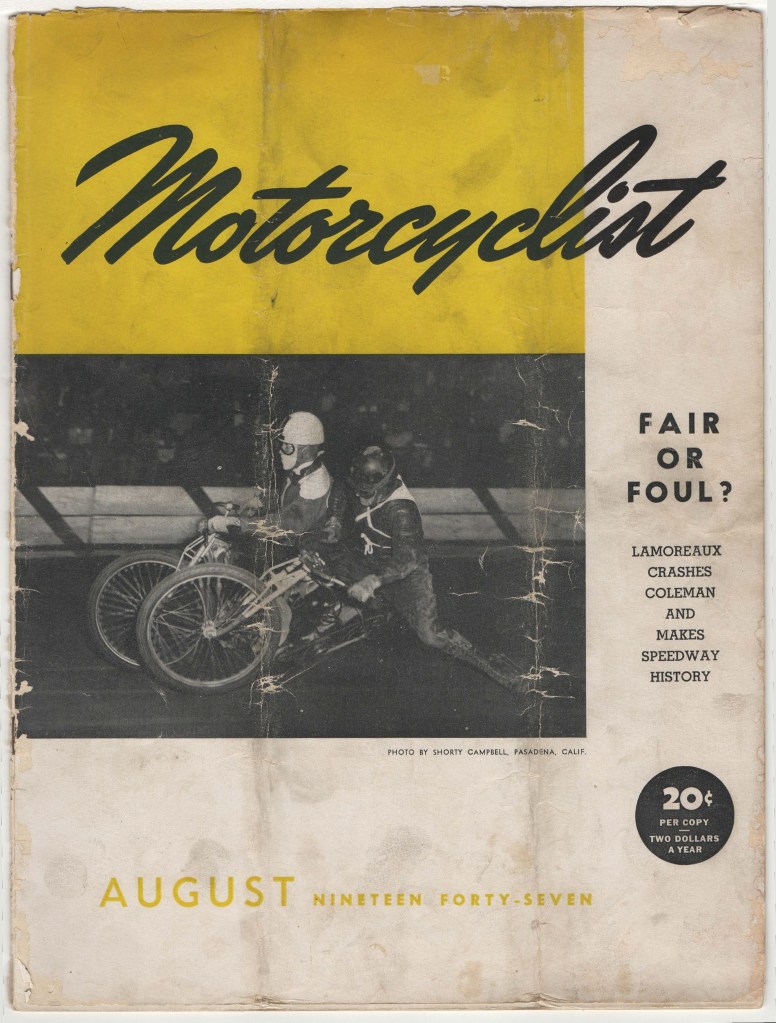

‘HOLLISTER’, MOTORCYCLIST, AUGUST, 1947

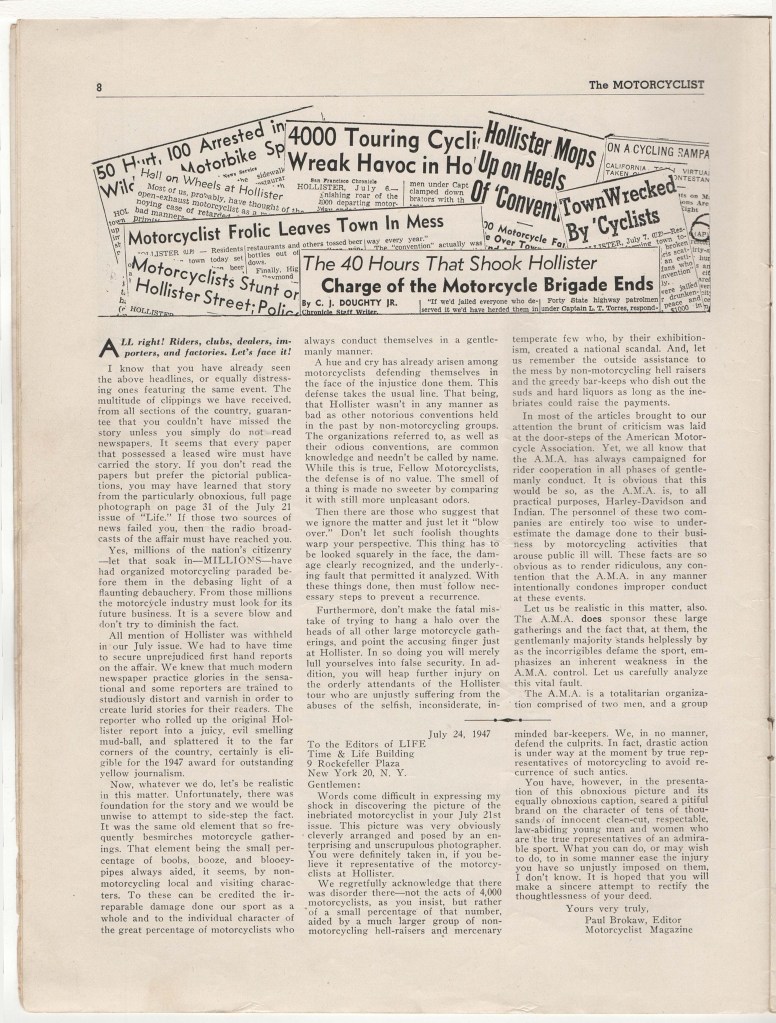

Granted, LIFE‘s coverage of the Hollister affair was pretty lurid, but Motorcyclist editor Paul Brokaw is no slouch in producing purple prose. He laments the fact that ‘millions of the nation’s citizenry — let that soak in — MILLIONS — have had organized motorcycling paraded before them in the debasing light of a flaunting debauchery.’

A flaunting debauchery? 🤷🏻♀️

He goes on to blast the unnamed reporter ‘who rolled up the original Hollister report into a juicy, evil smelling mud-ball, and splattered it to the far corners of the country,’ and nominates the hapless wretch for ‘the 1947 award for outstanding yellow journalism.’

I also love the line about ‘boobs, booze and blooey-pipes.’ Brokaw does have a way with words! 🙄

Brokaw then spends the remainder of his ink and column inches on a proposed reformation of the American Motorcycle Association*, which he blames, sotto voce, for not reining in ‘the abuses of the selfish, inconsiderate, intemperate few who, by their exhibitionism, created a national scandal.’

* The AMA is now the American Motorcyclist Association, which claims to be a ‘motorcyclists’ rights organization.’ However, the Association was originally formed by motorcycle manufacturers, to protect their interests against anti-motorcycling legislation that might impact their bottom line. In 1947, the AMA was little more than a mouthpiece for the Indian and Harley-Davidson companies.

Brokaw’s argument against the AMA is a bit convoluted, but he apparently feels their ‘totalitarian organization’ and its ‘fear of losing one iota of control’ causes the leadership, such as it is, to treat its constituents like ‘irresponsible adolescents.’ In his view, this brings on ‘a tendency of motorcyclists to relax into indifference, and look to the National organization (which exists in name only) to pull their chestnuts out of the fire.’ Brokaw feels that local control of events would inspire clubmen to rise up and hold the line against those ‘incorrigibles (who) defame the sport’ of motorcycling.

I was really hoping this Motorcyclist article might have some hidden gem – maybe even the elusive statement attributed to the AMA about 99% of motorcyclists being fine, upstanding citizens – but no. 😒 Instead, we get a self-serving screed about protecting the motorcycle industry by foisting responsibility off on rank-and-file members of the industry’s lobbying organization. 🙄

I had also hoped I might find the September 1947 issue of Motorcyclist, to see what readers thought of the Hollister debacle and Brokaw’s editorializing, but have yet to locate a copy. I can tell you that nothing appeared in the October and later 1947 issues, which I have at hand.

The hunt continues! 😎 Meanwhile, the Hollister story grows legs.

CYCLISTS’ RAID, Harper’s, January, 1951

The ‘riot’ at Hollister probably would have faded into the mists of time and memory, had it not been for Barney Peterson’s photograph, but the next stage in the evolution of the biker image was even more nefarious. A hack named Frank Rooney took the bare bones of what happened at Hollister and fashioned them into a lengthy, perverse short story titled ‘Cyclists’ Raid‘.

I am convinced the title’s echoing of LIFE‘s ‘Cyclist’s Holiday’ is not a coincidence.

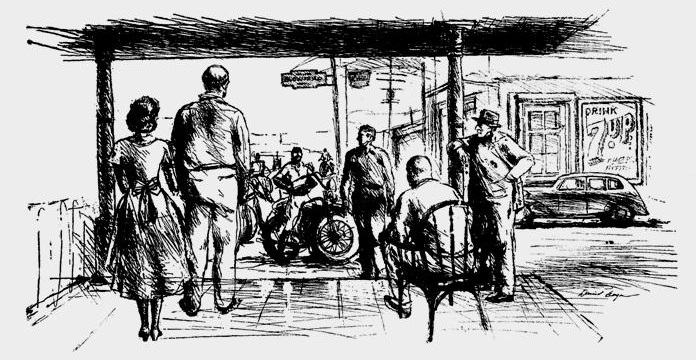

In his lurid saga, Rooney portrays the bikers as a paramilitary pack of marauders who chose the small nameless town from a list of possible destinations, and even did reconnaissance in advance of their arrival, going so far as to learn the names of hotel keepers and filling station managers. They ride into town in formation aboard matching motorcycles, and their leader, ‘Gar Simpson’, declares them to be ‘Troop B of the Angeleno Motorcycle Club.’ In casual conversation, Simpson reveals the club’s plan to expand across California (‘We’re forming Troop G now.’) and other states: ‘Nevada — Arizona — Colorado — Wyoming.’

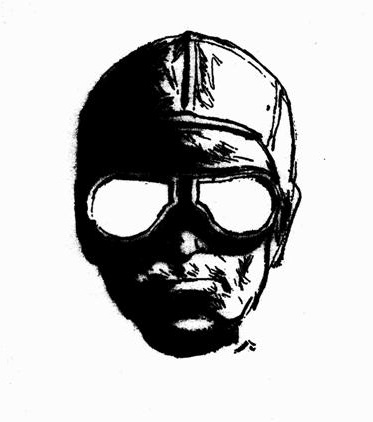

The riders quickly take over the accommodations in town, including the hotel operated by the story’s main character, Joel Bleeker, a widowed former Army officer and combat veteran with a comely seventeen-year-old daughter. The club members proceed to drink, to sing raucous songs, to ride their motorcycles up and down the street (and eventually the sidewalks), but never ever remove the green-lensed riding goggles they all wear, even at night, even inside the dining hall of Bleeker’s inn.

This is crucial to Rooney’s telling, because the goggles allow individual riders to remain:

‘standardized figurines, seeking in each other a willful loss of identity, dividing themselves equally among one another until there was only a single mythical figure, unspeakably sterile….‘

….so much so that when the ‘raid’ comes to its inevitably violent climax — a freak motorcycle crash which kill’s Bleeker’s beautiful daughter — Bleeker and his outraged townsfolk have no one to blame but themselves. The nameless, faceless riders are able to mount up and ride out of town, exempt from consequence by reason of their numbers and unremarkable sameness.

Rooney’s story appeared in Harper’s, a popular magazine that arrived by post in many American homes, issue after issue. It could not help but reinforce the ‘lesson’ of LIFE‘s ‘Cyclist’s Holiday’ pic: ‘Martha, those goddamned bikers are bad news!‘

A complete scan of the story ‘Cyclists’ Raid’, as published, can be read here.

THE WILD ONE, Stanley Kramer, et alia, December 30, 1953

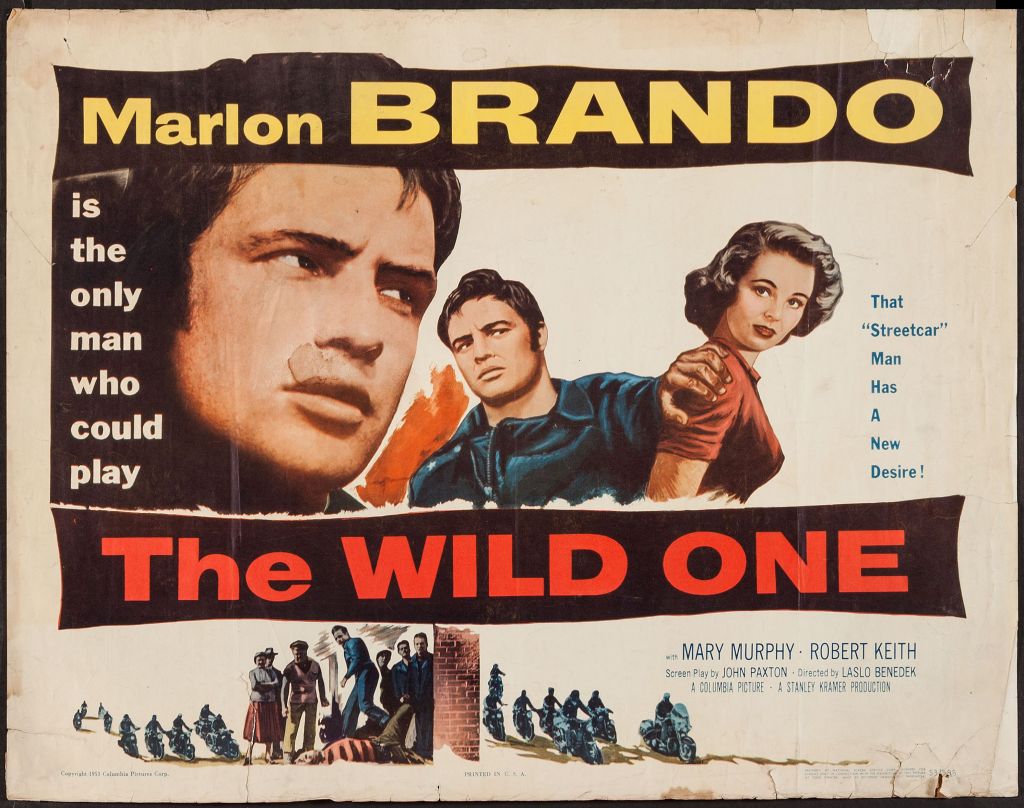

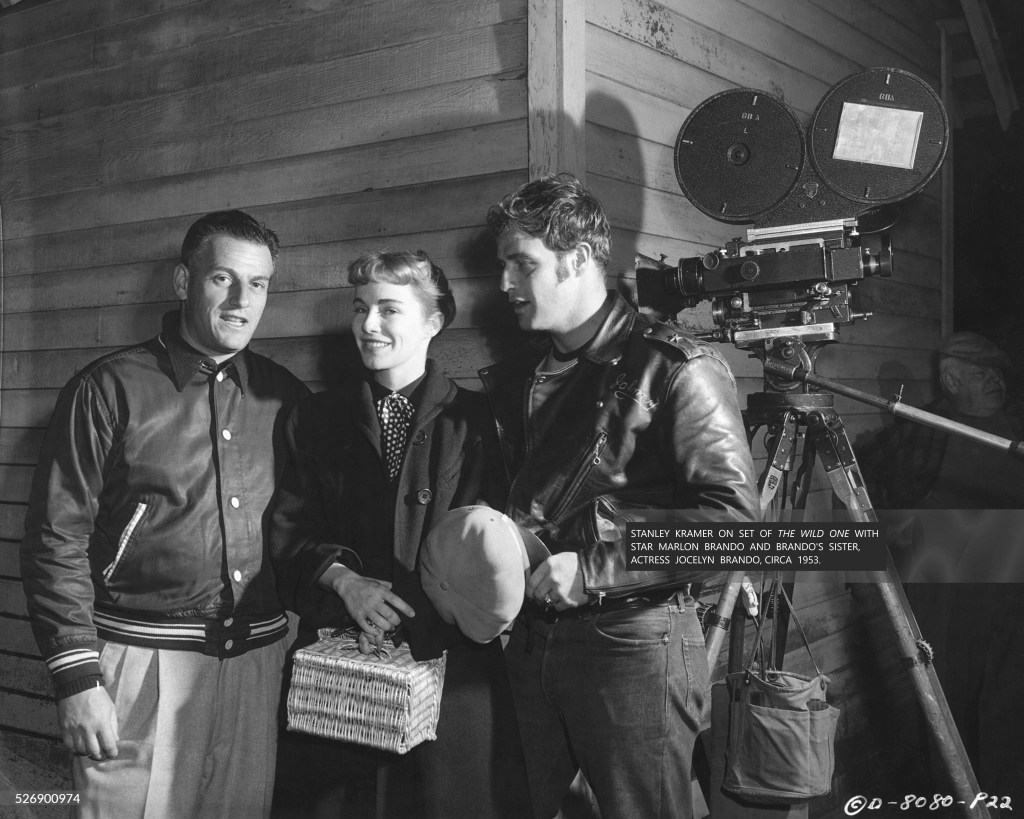

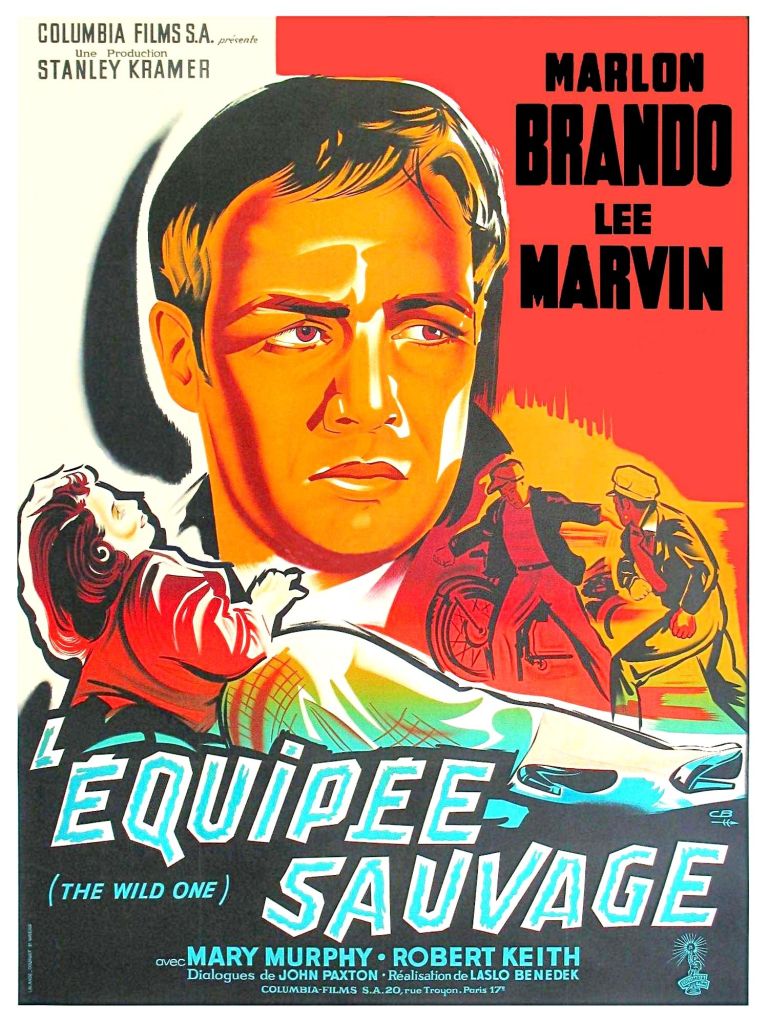

Rooney’s story, dripping with pathos and armchair psychology, caught the eye of filmmaker Stanley Kramer, who used the Hollister stories as inspiration for his 1953 Marlon Brando vehicle, The Wild One, co-starring Lee Marvin, Mary Murphy and, in an uncredited role, character actor Alvy Moore, best known for his portrayal of county agricultural agent Hank Kimball on the 1960s television show Green Acres.

Kramer interviewed people who actually attended the July 4th gathering at Hollister, and came away with a clear idea of the story he wished to tell.

A script was commissioned. However, it placed at least some of the blame for the events on the townspeople themselves, who invited the bikers in, tolerated the more benign hijinks they engaged in, and profited from sales of alcohol, food and other commodities. Censors rejected the script as ‘pro-Communist’, in that it made money-grubbing merchants the bad guys. We all know that anyone making money is, by definition, a hero, right? 🙄

Kramer caved, and as a result, we ended up with a bowdlerized version of the story Kramer wanted to tell. The true anti-heroes of Hollister — those brave young men just back from a grueling war, eager to recapture the camaraderie of military life, celebrate their survival and blow off years’ worth of steam — were replaced by Marlon Brando, as stiff as his brand-new Levi’s and monogrammed Perfecto leather jacket, portraying ‘Johnny Strabler’ as a mewling teenager riven with Daddy issues, riding a shiny new British bike, mumbling already-dated ‘hep cat’ slang and mooning over Mary Murphy’s more mature waitress.

Meanwhile, Lee Marvin, an actual combat veteran with a Purple Heart to his credit, and a real-life rider himself, acted the ‘villain’ of the piece. In ‘Chino’, Marvin channeled the essence of ‘Wino Willie’ Forkner. He rode into town astride a road-weary Harley-Davidson Big Twin, clad in military surplus and thrift store garments the way many of the men at Hollister had been, waving a cigar and loudly greeting old friends.

Johnny Strabler was a dilettante, a poseur. Chino was a fuckin’ honest-to-god biker. Johnny’s leather jacket may rightly be considered iconic — it is a fashion staple to this day, even amongst people who wouldn’t go within ten feet of a motorcycle — but so is Lee Marvin’s portrayal of Chino. Talk to bikers you know. How many of ’em wanted to be Johnny Strabler when they grew up? and how many wanted to be Chino? I can tell you my answer!

HIGHWAY PATROL

There’s another chapter to this story, discovered after I completed my post about Hollister. If you’re interested, there’s a link at the bottom about an episode of the television series Highway Patrol that aired in April of 1956. Check it out!

AND SO….

I geek out about this stuff because I love our history as motorcyclists — all the influences that went into creating our lifestyle and all the ways that lifestyle is portrayed, interpreted and further influenced by attention from media and popular culture. The chain of events that lead from World War Two to Hollister, from Hollister to Harper’s, and from Harper’s to Hollywood, are just part of the fascinating origin story we all share.

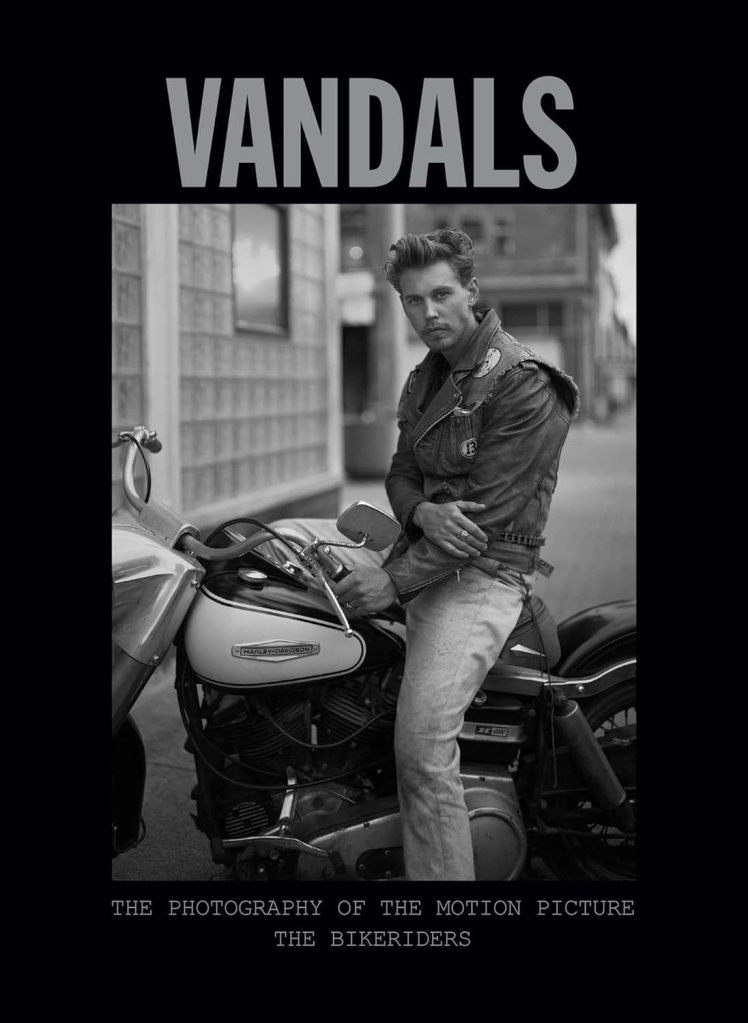

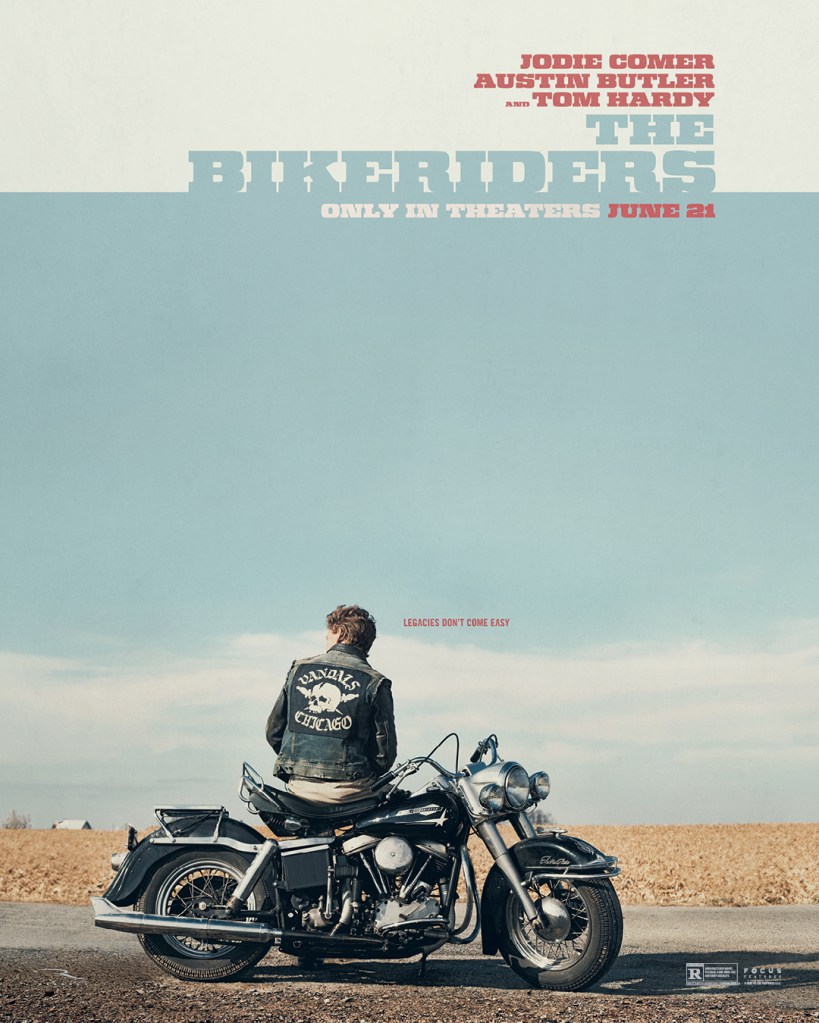

As I write this, we are less than two weeks from the premiere of yet another biker movie; an A-list Hollywood production starring well-known actors like Austin Butler, Tom Hardy, Jody Comer, Norman Reedus and Michael Shannon.+ The Bikeriders, loosely based on photo-journalist Danny Lyon’s seminal 1968 book of the same title, promises to be yet another milestone in our unfolding story. I already have my tickets, and can’t wait to see what comes up on the big screen!

* Congreve, William The Mourning Bride, 1697. The original lines read ‘Music has charms to soothe a savage breast, to soften Rocks, or bend a knotted Oak.’

+ Just this afternoon, I received my copy of The Vandals: The Photography of the Motion Picture ‘The Bikeriders’. Woo-hoo!